Ethical storytelling: An approach to ensuring truthful community representation and ownership

Why stories and representation matter

Storytelling is a powerful tool that’s been used since the beginning of time. Historically, understanding morals was often at the heart of why stories were told, reinforcing positive behaviours and encouraging us to connect and evolve as human beings. In line with storytelling, representation is how we make sense of ourselves and our surroundings, including our knowledge of the world.

But the reasons for storytelling and representation can vary, particularly in the international development sector where meeting the needs of an audience - mainly those who give funds - is often prioritised. Most of us will have seen the all too familiar adverts showing an African child with a seemingly full stomach held by a delicate frame. Images like these shape audience perceptions and understandings of international development and, most importantly, the places and people shown in the images.

The recent BBC News article, “We knew Christmas before you' - the Band Aid fallout" discusses the Christmas hit’s problematic lyrics and over-simplistic, stereotypical representation of an entire continent - describing it as a place "where nothing ever grows; no rain nor rivers flow". In a statement by Bond, a UK network for organisations working in international development, Lena Bheeroo, head of anti-racism and equity, said “Initiatives like Band Aid 40 perpetuate outdated narratives, reinforce racism and colonial attitudes that strip people of their dignity and agency”

This oversimplification offers the audience - often sitting outside of the continent - little room for meaning-making. These decontextualized depictions of deprivation limit engagement with the images and wider context. Intentions, language and cognitive biases continue to influence the storytelling process, putting the authenticity, intention and ownership of stories into question and in turn reinforcing harmful stereotypes and fuelling misconceptions.

How we can support truthful representation

Ethical storytelling pursues a deeper understanding of historical and cultural issues helping to guide the storytelling process. Telling ethical stories is to adopt a new approach that consciously tries to move away from harmful, stereotypical narratives. It considers the impact of language. For example, words such as “vulnerable” are often used, even when the communities themselves do not always see themselves as such. Language can be used to perpetuate stereotypes and power imbalances, but it can also help shift narrative and influence change.

As NGOs who depend on stories to communicate the inspiration and impact that drive our shared work, not only do we have a collective responsibility to create and share contextualised and ethical stories, but to ensure that communities are central to the storytelling process.

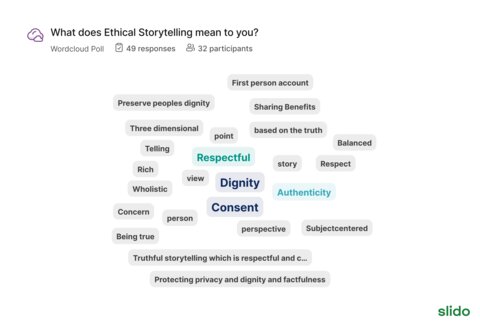

The NNN Communications Cross-Cutting Group opened a conversation on ethical storytelling at the recent NNN conference in Kuala Lumpur, inviting all NNN members to continue the dialogue and acknowledge our responsibility in sharing broader narratives with our audiences.

Stories communities can own

One of the key questions arising from the interactive workshop on ethical storytelling was how to champion country ownership of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) when communities do not own their stories. The workshop aimed to inspire open conversations about ethical storytelling and acknowledge how we, as the broader NTD community and within our respective organisations, can better implement ethical storytelling principles in our work and support a more truthful representation of persons affected by NTDs.

Brigitte Perenyi, a documentary story producer and advocate with a special focus on ethical storytelling, encouraged the audience to consider, “Who owns the story? Who sees the story? And by telling the story, whose needs are we meeting?”. Through the use of ongoing informed consent, Brigitte highlighted how critical it is for individuals to understand how their story will be used and shared, building authentic relationships based on trust that come from deep community conversations. This breaks barriers by creating an environment that welcomes perspectives and experiences of those living with NTDs. Brigitte reinforced the implications of distorting narratives, shedding light on how to support truthful representation of communities, with a focus on engaging through conversation and knowledge sharing, rather than passive observation. She said, "The goal is to use storytelling to listen – providing a platform for people with lived expertise to share their opinions and ideas, as well as how they are playing a role in shaping solutions”.

Who owns the story?

Edna Mosiara, Communications Officer at Amref Health Africa, captivated the audience with compelling research, Who Owns the Story?, demonstrating the transformative power of ethical, community-led storytelling in fostering authenticity, trust, and deeper donor engagement. Edna urged organizations to prioritize trust-building and collaboration, redefining success as a process of mutual respect and meaningful connection rather than polished outputs. She shared practical strategies, such as rethinking consent practices, incorporating first-person testimonies, and partnering with local creatives to ensure storytelling reflects community ownership and integrity. Her presentation championed approaches that position communities as co-creators of their stories, inspiring a future where storytelling becomes a tool for transformative impact and equity.

Planting the seed to embrace ethical storytelling

The workshop included breakouts which sought to tackle different ideas and complexities surrounding ethical storytelling. Online attendees looked at the fluidity of language, considering how words and phrases might be received differently depending on context and circumstances. Phrases we hear often in international development, such as global north/south, capacity building, and in the field/on the ground, divided opinions. Of interest, the use of the term ‘neglected tropical diseases’ itself was also put into question. In contrast, the online attendees showed support for phrases like locally-led development and people with lived experiences.

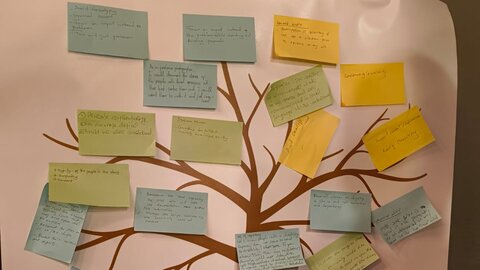

The in-person breakout session began by exploring how each role involved in the storytelling process can implement the principles of ethical storytelling to ‘do no harm’. The audience was later introduced to a real-life scenario of gathering stories, encouraging them to consider issues surrounding consent and safeguarding, and highlighting the value in collaborating with people in the communities.

Five key takeaways

- Treat a story in its entirety

- Avoid set-in-stone briefs for what a funder or team is expecting to receive, instead be open to a diverse range of stories and avoid the single negative narrative

- Ongoing informed consent is a process

- Go beyond forms and instead continuously obtain and reaffirm consent from individuals as you gather, share, and use their stories or personal information

- Build trust and a relationship with communities through conversation and mutual respect

- Spend time with people in the communities to have conversations that lead to knowledge-sharing and a real understanding of how they want to be represented in their own stories

- Follow the ethical principles of ‘do no harm’ to encourage a more participatory and truthful representation of people with lived experience.

- Ensure the stories we share are those that give agency so that communities can have true ownership of them

- Communities should not be seen as subjects or pasive participants but as co-creators in the story gathering and storytelling process. Looking beyond KPIs and vanity metrics, it is through investing in relationships and fostering an environment of trust, authenticity and meaningful engagement with communities that real impact is created and shared.